How cheqd is approaching its tokenomics for secure and trusted data ecosystems

Co-authored by Fraser Edwards and Ankur Banerjee

Identity is a construct of its subject (person, company, virtual thing) and surroundings (birth, country borders, online games). Identity, therefore, varies in how it manifests (passports, self-declared data or an outfit, real or virtual) but also how it is commercialised (or not).

Across the world, identity has been commercialised in too many ways to count. These range from transparent and simple relationships like paying for a passport to complex and opaque models like targeted advertising.

Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) will replicate some of these models, destroy others and create entirely new ones too. Creating entirely new models is what we at cheqd are truly excited about.

In this blog post, we will explain some of the commercial models prevalent in digital identity, and how cheqd is building new models for the world of SSI.

First, let’s look at breaking down the current landscape…

How many parties are involved?

The full gamut of commercial models are first easiest to break down by the number of parties involved and the flow of information (abstracting some of the complexities in the background):

- Uni-lateral, e.g. an International Certificate of Vaccination issued to a patient by their doctor. The details included in the certificate are generated by the doctor.

- Bi-lateral, e.g. a Passport Office taking information from applicants to verify them before issuing them with a passport. In this scenario, it is likely that some of the information provided by the applicant is already known to the Passport Office, and there are details generated by the Passport Office.

- Multi-lateral, e.g. BankID in Sweden where Know Your Customer (KYC), verification, and authentication are mutualised between banks (and now others).

Note here that the data subject, the individual or company whom the data is about, is always involved at some level in the exchanges above.

We know there are many other possible models, please do let us know in comments any particular others that should be called out.

Who pays whom in identity flows?

While the number of parties involved in an exchange is an important aspect, commercial models for digital identity can also be categorised based on the pricing construct applied between the parties involved in digital identity exchange.

Paid for by the individual/company (or the “identity subject”)

Free

Free, as in beer, to the individual. This is a credential that is given to an individual or company without any money changing hands.

An example of this would be a tax registration number or Social Security Number, which an individual or a company can get without paying anything.

Freemium

Most interactions are free, but some are paid.

An example of this would be a university degree, where the original degree is provided for no additional cost (beyond tuition fees), but additional copies of the degree need to be paid for.

TRANSACTIONAL

The issuer is paid per issuance or verification.

An example of this would be a passport application, where the applicant pays a one-time fee to the passport office to acquire the latest valid document.

Data mining

The interactions an individual/company has with an organisation is recorded, with the metadata and behaviour used to create weak identity profiles. The interactions appear free to the individual or company, but their identity profile is monetised by selling inferences to other companies.

An example of this is programmatic targeted advertising, which are the intrusive ads we often come across online controlled by large ad networks. Some of the largest ones are run by Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple.

With targeted advertising, “You’re not the customer, you’re the product.”

Paid by verifying organisation(s), free for individual/company

DIRECT RELATIONSHIP WITH ONE ORGANISATION

An individual or company provides identity attributes to an organisation that needs to verify them. The organisation in turn bears the costs of the checks or pays someone else to do it. An example is the usual Know Your Customer (KYC) process for an individual/company to open a bank account. While the individual/company doesn’t pay for any identity verification checks, the bank (verifying organisation, in this case) might pay third parties to carry out checks on its behalf. These third parties are personal identity verification providers such as FinClusive, Onfido, Alloy, HireRight etc or corporate identity verification providers such as Dun & Bradstreet. These identity providers in turn often get data from their own sources, such as government records. This model can be further extended based on what pricing basis is the verifying organisation is charged at by the third parties:

- Pay-as-you-go: Each interaction is charged on a per-check basis (manual or per-API call)

- Tiered subscriptions: Verifying organisations pay fees in blocks based on usage

- All-you-can-eat: Verifying organisations pay a single fee regardless of how many ID verification checks they carry out.

MUTUALISED COSTS ACROSS MULTIPLE ORGANISATIONS

The cost of carrying out identity verification is split across the benefiting organisations, either equally or in proportion to use. This is often an extension of the direct model above. An example of this would be a consortium like BankID in Sweden, where the cost of KYC is spread across different organisations. The individual/company also does not pay in this scenario. Another example of this is how credit bureaus such as Experian,Equifax, TransUnion pool together information from financial institutions, but then re-sell the transformed data to other companies.

The missing individual

In each of the models above, there are organisations doing work to check identity attributes. The outcome of this is they add the weight of their authority, which is valuable to an individual/company. Each of the models above has a set of advantages and trade-offs, whether it be in cost, efficiency, privacy, or security. There is tremendous value in this variety of models by aligning incentives for those involved.

Current identity solutions largely put the incentives of issuing/verifying organisations over the individual/company. The identity subject (i.e., individual or company) at best has to directly pay (sometimes prohibitive) fees to acquire documents, and at worst often have no real control over their own data (as often in targeted advertising.)

Many further axes could be applied to the models above. One, in particular, we want to highlight is that the costs associated with acquiring and verifying identity depend on geographical as well as industry context.

Costs that are considered affordable in one country can be extortionate in others. Even within a country, affordability and access to verified identity may be prohibitive for disadvantaged demographics. The unfortunate consequence is exclusion due to a lack of verified identity that impacts large parts of society.

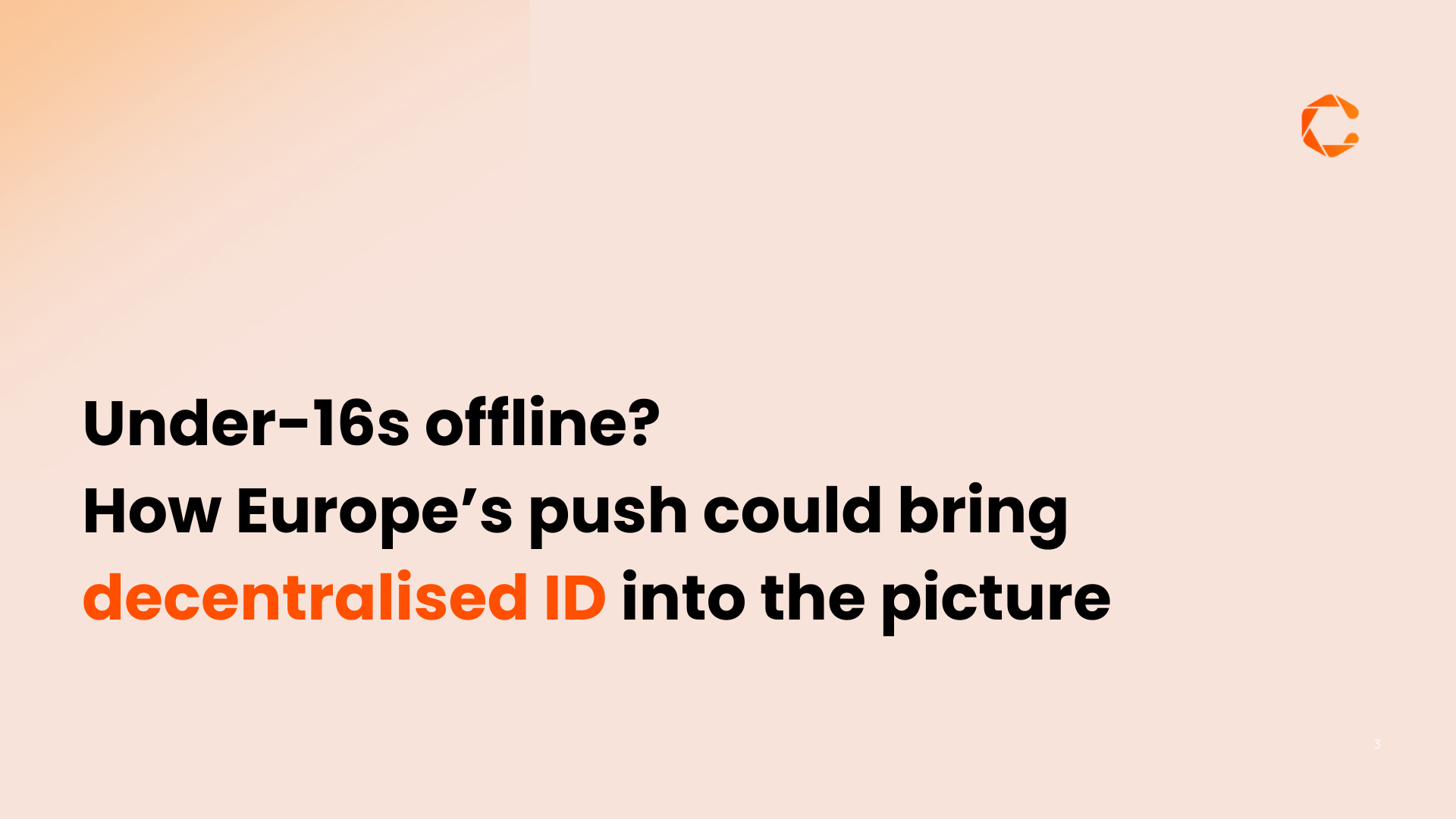

The virtuous flywheel for the trusted digital identity

Self-sovereign identity is a powerful transformational force that changes the balance of power in the favour of identity subjects (individuals/companies). Any commercial models for SSI needs to reward the identity subjects for participation, increase inclusion through easier access, and disincentive undesirable data-sharing behaviours.

On the other hand, the time and resource cost an issuing/verifying organisation incurs must not be ignored for a viable and sustainable self-sovereign identity ecosystem.

For instance, government-issued credentials should be made free / as cheap as possible to acquire as they are funded through taxes and/or one-off fees. This is crucial as government-issued credentials are often the genesis of trusted data in many industry contexts.

However, in other scenarios where an issuing/verifying organisation is not a publicly-funded organisation, we do see an unmet need for compensating organisations that carry out the work of verifying digital identity. These organisations are the root of trust that make SSI credentials held by an identity subject more trustworthy and have greater utility.

cheqd’s vision on the virtuous flywheel of self-sovereign identity growth

We believe this will create a virtuous flywheel for self-sovereign identity growth, where:

- More issuing organisations are incentivised to give “back” trusted data to identity subjects. Data that belonged to or originated from identity subjects in the first place, but with the stamp of authority that the issuing organisation brings.

- With more SSI credentials in circulation, more organisations will accept SSI credentials as it is an easier, more efficient, and more secure way of getting trusted data with the consent of the identity subject.

- Growth in usage will attract more product companies (like cheqd) who build self-sovereign identity software, enrich features and functionality, and integrate SSI into their apps and services.

- As SSI credentials become more common, the genesis data needed to verify identity will become cheaper, lowering the cost structure for creating trusted data.

- Lower cost structures for creating trusted data will result in lower prices over time — than current, sometimes prohibitively expensive methods — for consuming verified identity data.

- Lower prices to consume trusted data will give individuals and companies a richer ecosystem of organisations and services that accept SSI, leading to a better user experience that is more private and secure than the current relationship with how their data is used.

(N.B. We acknowledge we are using an analogy from Amazon here. While we do not necessarily agree with Amazon’s corporate stance on some issues, we do believe this is a useful analogy to explain how cheqd’s commercial model for self-sovereign identity will increase SSI adoption and growth. In the diagram, we use SSI as a catch-all to include verifiable credentials.)

Our approach to building a viable self-sovereign identity token network

cheqd is already building towards launching a standards-compliant, incentivised SSI network in 2021. The cheqd network will have a token that facilitates the virtuous flywheel. We went into some depth on why SSI models such as the Trust Over IP stack need an extension with an economic model in our previous blog post.

We are frequently asked for a simple description of our tokenomics model for the cheqd SSI network, but this ignores the complexity of how something deeply personal as identity is exchanged between different parties today. Hopefully, our explanation of the commercial models for digital identity will give a flavour for how diverse the interactions are.

All of these factors create a hugely complex marketplace to create a tokenomics model.

We believe at cheqd that a one-size-fits-all commercial model for digital identity will not accommodate the richness of current and future SSI use cases. We are approaching this problem by building a base layer that supports a variety of different tokenomics plug-ins, which can be customised based on the context of the ecosystem it is serving.

The analogy we like to use for cheqd’s approach with customisable tokenomics is trade rules between countries:

- Bi-lateral or multi-lateral trade agreements: Specific agreements between countries for trade, setting out requirements, tariffs and the like.

In the context of self-sovereign identity: Ecosystems (geographical, industry-based) should be able to define what economic policies they want to adopt, such as price points for credentials (including free and freemium), governance rules, - World Trade Organisation Rules: Where no bi-lateral or multi-lateral trade agreements exist, there are international baseline rules to fall back on.

In the context of self-sovereign identity: When SSI credentials hop across between different ecosystems, there are baseline economic policies they can fall back to, thus making them portable across different ecosystems.

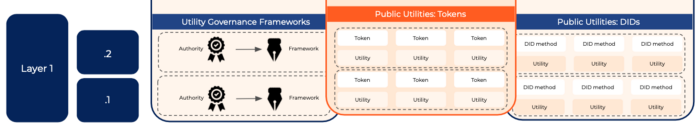

cheqd’s suggested expansion of the Trust Over IP Stack with an economic layer

Using the numbering for Layers from our previous blog on the Trust Over IP stack, in the cheqd SSI network our vision is to translate this into:

- Layer 1.1: A base layer of tokenomics so that any individual or organisation can interact with any other, regardless of industry or country. (“World Trade Organisation rules”)

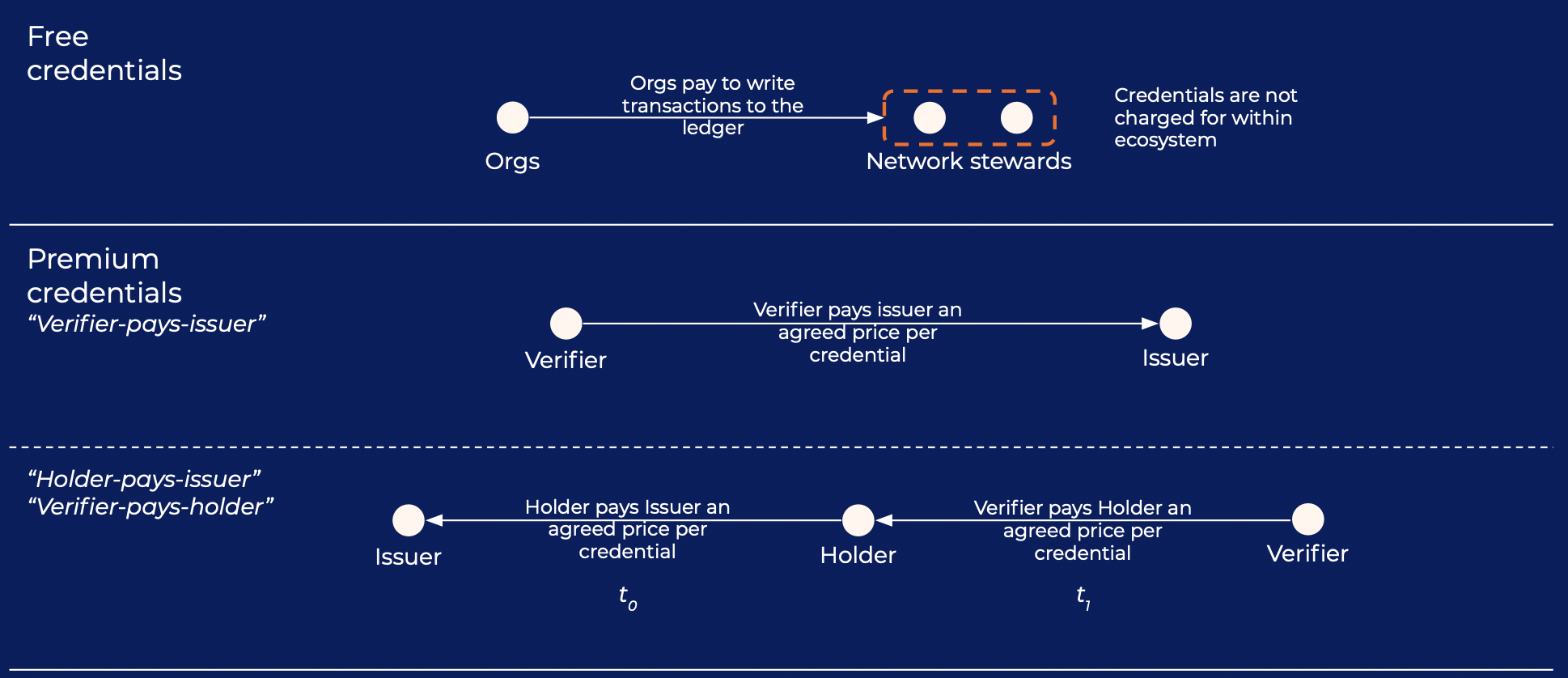

- Layer 1.2: Customisable tokenomics plugins such as: “verifier pays holder“, “verifier pays issuer“ or subscription models so that each ecosystem can define its incentives to suit itself and its users the best. (“Bi-lateral or multi-lateral rules”)

Examples of commercial models in self-sovereign identity

We believe this will jumpstart a global, collaborative, vision for SSI whilst accounting for the complexity and nuance we have outlined above in terms of commercial models. We see the tokenomics plug-ins specifically dovetailing with the Trust over IP metamodel for governance frameworks to facilitate the easy creation of multiple ecosystems (such as Trinsic Ecosystems).

In future blog posts, we plan on explaining our vision for how governance would work on the cheqd SSI network, as well as expanding on our ideas about the virtuous flywheel of SSI growth with a deep dive on the new commercial models that can exist in this space.