A deep dive into the fundamentals of what a Trusted Data Market is and how cheqd’s infrastructure enables them.

This is part of a series, read the second blog ‘The role of cheqd in Trusted Data markets’ here.

In short, a “Trusted Data Market” is a vision for both consumers and businesses where the paradigm of data ownership is inverted to the user, trust is verifiable, and can be transacted upon within a privacy-preserving data market.¹

Introduction

If you look up the word “trust” in the dictionary, the first definition is typically one about general trust between two parties, but almost always, the second definition is a financial one. Take, for example, the language around finance; the United States is backed “by the full faith and credit” of the U.S. government. “Credit,” from the Latin credere, literally means “to trust.” Trust is known to be fundamental to better economic outcomes² and we all trust in others and reciprocate that trust with trustworthy actions as part of our everyday lives. Moreover, economic historians debate the relative importance of models of trade growth and the importance of capital infusion to fuel innovation. But where there is broad agreement is in the central notion that goes back to civilisation’s origin: trust undergirds cooperative behaviour. But what is trust’s central role in markets? And how could verifiable data change trust’s role in markets to form a new data paradigm?

Defining Trust

Philosophers have an important definition of what ‘trust” is. Most agree the dominant paradigm of trust is “interpersonal” and this type of trust is a type of reliance, although it is not mere reliance.³ Rather, trust involves reliance “plus some extra factor.”⁴ Although this definition is lacking when applied to trust in current data markets, we will explore later its applicability within a trusted data market.

This extra factor typically concerns why the trustor (i.e., the one trusting) ought to rely on the trustee to be willing to do what they are trusted to do. This is further conditioned by another layer of trust: whether the trustor is optimistic that the trustee will have a “good” motive for acting. This is especially important should the trusted interaction involve a transactional relationship (the exchange of assets or risk), to optimise incentive alignment within a market context.

This is demonstrated in the logic of why one should trust someone.

T(x,y) = x trusts y

R(x,y) = x relies on y

E(x,y) = x ought to believe there is an ‘extra factor’ for trusting y

W(x,y) = y is willing to do what they are trusted to do

M(x,y) = y acts with good motive

For all x and y,

T(x,y) → [R(x,y) ∧ E(x,y) ∧ W(y) ∧ (T(x,y) → M(y))]

This translates to: for all x and y, x trusts y iff (if and only if) x relies on y and believes there is an extra factor for trusting y and y is willing to do what they are trusted to do (not dependent on x trusting y) and if x trusts y, then x believes that y has a good motive for acting. This logic breaks down if y would not be willing to do what they were originally trusted to do and/or y acts with a “bad” motive.

Critically, to establish these relations as “trusted,” time and repetition are necessary. The more “trusted interactions” are performed successfully, the more likely one can safely assume trust as I can likely assign a ‘good’ motive for acting, and admit a history of actions than consistently show y is willing to do what they are trusted to do.

In this blog, we’ll explore how a market dynamic could shape if certain trust conditions in our introduction became verifiable from inception, what this subsequently could mean for time-to-reliance to form trust, and the consequences in terms of transparency, accountability, and reliability this could entail. We will then explore how this could form a “Trusted Data Market.”

The Role of Trust in Markets

Trust is, and always has been, an essential component of markets. Therefore, we must ascertain why trust formed in markets, and why sociologists and anthropologists cite the advent of market economies as representing a significant break in the organisation of human societies.

From an economist’s perspective, markets represent a transition from a system where product distribution was based on personal relationships to one where distribution is governed by transparent rules. While these rules are necessary to ensure that markets operate effectively, trust is also crucial to ensure that transactions are conducted in good faith, and to promote compliance with market regulations. The rules themselves now represent a ‘shared truth’ which replaced the previous social contracts and interpersonal relationships that pre-dated market economies.⁵

Primarily, trust reduces the risk of opportunistic behaviour within rule-based frameworks. When buyers and sellers trust each other to act in good faith, they are more likely to engage in mutually beneficial transactions. As described above, these ‘trusted interactions’ form a basis for trust over time. Therefore, trust is an important property for promoting compliance with market regulations to ensure that the market functions efficiently and that all participants can compete fairly. Concerning data, trust is also critical for promoting transparency and accountability in markets with rules. When buyers and sellers trust each other, to be honest, and transparent in their transactions, they are more likely to provide accurate information about the goods and services they offer. This promotes transparency in the market and helps to ensure that all parties have access to the information they need to make informed decisions. Moreover, trust can also foster self-regulation and promote agency, defined by Hickman et al. as:

“… intentionality, responsible for defining strategies and plans; anticipation, related to temporality, in which the future tense represents a motivational guide, driving force of prospective acts to reach goals; self-regulation, which are personal patterns of behaviours that monitor and regulate their actions; self-reflection, responsible for self-inquiry into the value and meaning of their actions.”⁶

And with agency undergirded by trust, businesses and individuals who are trusted by their peers are more likely to adhere to ethical standards and social norms.

For these advancements to occur, verifiable data could reduce the need for trust (its current role in markets), as defined by time + trusted interactions, by ensuring data integrity and authenticity, promoting fair competition, reducing fraud risk, improving transparency, and simplifying regulatory enforcement. Forming a powerful tool for modern rule-based markets’ efficiency and effectiveness and ability to innovate with new use cases, commercial models and trust dynamics.

Data in Markets

Data is well-referenced as the “new oil” of the digital economy. This is perhaps more evident than ever before as its driving innovations like Chat GPT, creating new knowledge and insights from various machine learning and reasoning techniques, and increasing efficiency in many fields.⁷

However, certain types of data markets are not transparent where the user is the product. Typically, consumers are not cognisant of what happens to their data, and without self-sovereign identity, cannot control data use.⁸ Researchers and academics have persuasively argued a legitimate trade of data in a “shadow market”⁹ has evolved, however, this “shadow market” (intermediary platforms that trade on subject’s data) is not lucrative for the subjects of data, but is for data controllers. This has presented a conflict and misalignment of incentives between consumers’ data rights, assumed privileges and increasing desire for privacy and the current market demands for data.

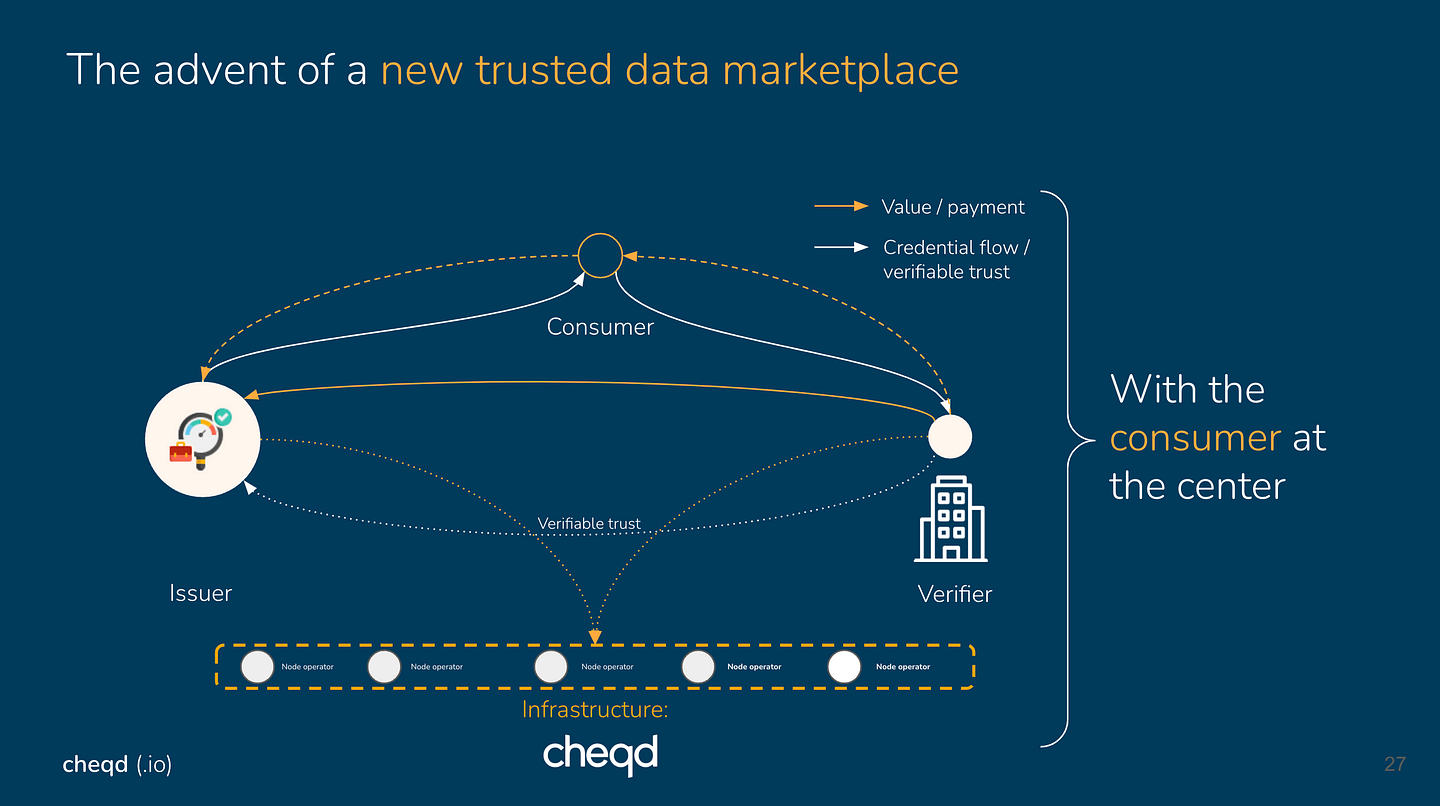

A vision for both consumers and businesses, where the paradigm of data ownership is inverted to the user, and trust is verifiable within a privacy-preserving data market¹⁰ is what we at cheqd refer to as a “Trusted Data Market” powered by cheqd’s infrastructure.

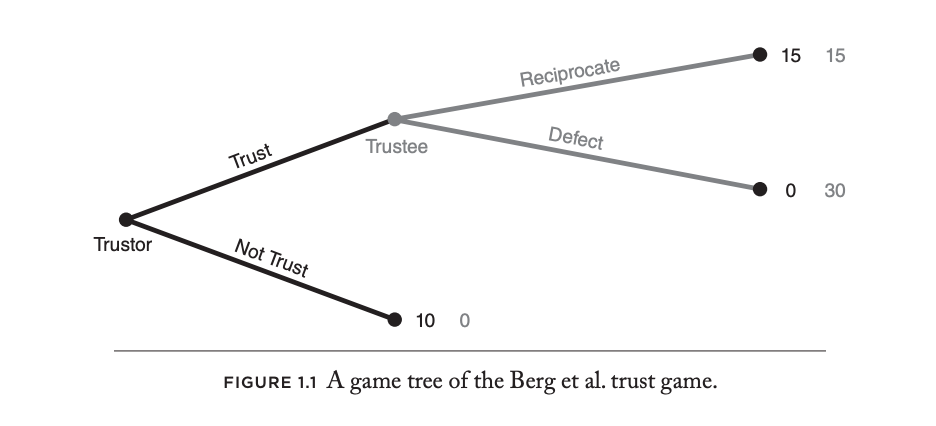

The Trust Game

Importantly, the “Trust Game” models how trust occurs in the context of a cooperative relationship with repeated interactions over time. In iterations of market dynamics where trust must be assumed, gained, reciprocated, and then maintained, we can only gage trust by how parties act within a transactional instance, and how the accumulation of these trusted interactions forms “trust” and creates dependencies on how those actions will affect cooperation in the future. Simultaneously, how market participants behave today is also determined by cooperative behaviour in the past.

In the Trust Game model, repeated interactions over time are the critical factor in determining whether those interactions can be fairly assumed as worthy of a trusted reputation. Players may initially be cautious and invest a small amount, and then gradually increase their investment as they learn more about the other player’s trustworthiness. This may not always lead to high levels of trust and cooperation between the players.

However, if verifiable trust is established from inception, players would have access to data about each other’s trustworthiness before the game begins. For example, they may have access to ratings or reviews from previous games, or other forms of verifiable data that indicate the other player’s trustworthiness, like data which is issued from a trusted issuer that provides assurance the information the player presents has an “extra factor” other plays can rely upon. This can create a positive expectation and lead to more initial trust between the players, reducing the need for a learning process to establish trust. Time-to-reliance within the market dynamic shifts, regardless of the use case as the verifying participant can assume the data is at base verifiable.

For example, in the Trust Game’s model, if the players have access to verifiable data indicating that the other player has a history of trustworthy behaviour in previous games, they may be more likely to invest a larger amount of money in the current game. This can lead to a higher degree of cooperation and reciprocity between the players, resulting in higher payoffs for both players and they may be more likely to view them in a positive light and exhibit more cooperative behaviour.

This also reduces the complexity of why a rational agent should trust someone. To travel back to our previous logic, let’s see how it becomes modified:

For all x and y,

T(x, y) if and only if [(R(x, y) ∧ P(x, y))]

where

P(x, y) = x has positive reasons (verifiable trust) to assume or validate that y is trustworthy.

Trusted Data Markets

In two essential references for this blog, Altman defines privacy as “the selective control of access to the self,”¹² and Mason describes the individual who trades private information about the self as a kind of currency in exchange for anticipated goods and services.¹³ Essentially, I should be able to exercise personal agency, select, control and subsequently act (for example, trade) upon information that accesses my personal data and determine with whom I share that access with. This is not a new digital precedent but has been deliberated on in terms of dignity, exceptionalism, and values by philosophers for centuries.¹⁴

Many other well-worked cheqd blogs on self-sovereign identity, trusted data, and cheqd’s payment infrastructure explain how self-sovereign identity and cheqd’s infrastructure can facilitate this paradigm, both from a technical and commercial perspective. What we’ll dive into in this blog is the relevance of this type of data, and selective control of it, to a market dynamic.

In a cheqd trusted data market, “holders” (users, companies, objects) have selective control, and their willingness to share data is dependent on a variety of factors, e.g: benefits, type of information, programming and culture.¹⁵

In “Trusted Data Markets,” companies issue verifiable data to holders, who in turn actively share their data with interested parties (known as “Verifiers”) who wish to verify that data. The reasoning behind this dynamic forming is multifold, but we will focus on commercial benefit for “Issuers”, and we will explore various use cases in subsequent blogs where Trusted Data Market dynamics form around a payment flow: “Verifier pays Issuer.”

Within a “shadow” data market, this payment has already formed, without the user, as we all already interact within Data Markets, but our data is traded upon without our selective control. With cheqd and self-sovereign identity, this paradigm is inverted via a privacy-preserving, standards-compliant data and payment infrastructure. This infrastructure forms the structure for both verifiable trust and payments to support the transactional flows of associated verified and trusted data within the format of verifiable credentials.

The “Issuer” issues Verifiable Data

The “Holder” receives this data, which can be trusted as 100% verifiably issued by the Issuer.

The “Holder” then presents said data (a Verifiable Credential) to the “Verifier/Receiver.

Upon presentation, in which the “Holder” maintains selective control, the Verifier can “check” the verifiability of the Verifiable Credential (the data), via cheqd’s network, and upon this “check” ascertain whether the data is: verifiability issued by the issuer, non-revoked, and of the correct standards.

It is via this “check” a privacy-preserving payment is released from the “Verifier/Receiver” to the “Issuer.” At no point within this market dynamic is selective control of the data removed from the “Holder” and at no point is the presentation of the “Holder’s” data gated by a payment wall.

The verifier can ascertain greater trust in the credential received, via the reputation of the issuer reducing time-to-trust and trust the data issued is from the issuer at genesis.

The price a Verifier is willing to pay correlates to the impact of Verifiable Trust on the market dynamic.

This price is set by the Issuer.

Crucially this solves two significant problems for data markets.

TIME-TO-RELIANCE TO ESTABLISH TRUST

SELECTIVE CONTROL WHILST MAINTAINING PRIVACY

Conclusion

Learn more

We will be following this initial blog with a deep dive into how cheqd’s infrastructure supports the advent of Trusted Data Markets, followed by specific use cases we’re exploring. Beginning with credit data.

If you’d like to learn more, please reach out to us directly: [email protected]

[1] Gkatzelis, V., Aperjis, C., & Huberman, B. A. (2015). Pricing private data. Electronic Markets, 25(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12525–015–0188–8

[2] Arrow, K. (1972). Gifts and exchanges. Philosophy and Public Affairs, I, 343–362, Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust. New York: Free Press, Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[3] Goldberg, Sanford C., (2020), “Trust and Reliance”, in Simon 2020: 97–108.

[4] Hawley, Katherine, (2014(, “Trust, Distrust and Commitment”, Noûs, 48(1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/nous.12000

[5] https://policyreview.info/open-abstracts/trust-trustless

[6] https://trustoverip.org/wp-content/uploads/Overcoming-Human-Harm-Challenges-in-Digital-Identity-Ecosystems-V1.0-2022-11-16.pdf pp. 30–32

[7] Spiekermann, S., Acquisti, A., Böhme, R., & Hui, K. L. (2015). The challenges of personal data markets and privacy. Electronic Markets, 25(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015- 0191–0

[8] Spiekermann, S., & Novotny, A. (2015). A vision for global privacy bridges: Technical and legal measures for international data markets. Computer Law and Security Review, 31(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.clsr.2015.01.009.

[9] Conger, S., Pratt, J. H., & Loch, K. D. (2013). Personal information privacy and emerging technologies. Information Systems Journal, 23(5), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2012.00402.x

[10] Gkatzelis, V., Aperjis, C., & Huberman, B. A. (2015). Pricing private data. Electronic Markets, 25(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12525–015–0188–8

[11] Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton, NJ: University Press, Princeton.

[12] Altman, I. (1976). Privacy — a conceptual analysis. Environment and Behavior, 8(1), 7–29.

[13] Mason, R.O., Mason, F., Conger, S. & Pratt, J.H. (2005). The connected home: poison or paradise. Proceedings of Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Honolulu, HI, August 5–10

[14] Floridi, Luciano, On Human Dignity and a Foundation for the Right to Privacy (April 26, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3839298 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3839298

[15] Hallam, C., & Zanella, G. (2017). Online self-disclosure: The privacy paradox explained as a temporally discounted balance between concerns and rewards. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.033.